Building for cross-browser compatibility

This is the third post of a multi-part series about developing the brand identity for Wismut Labs.

The previous post covered a number of design decisions made with regards to the overall style of the Wismut Labs brand. This post will focus on the actual building of the Wismut Labs website.

We don’t need no database

The site is built with Jekyll, a static site generator that supports markdown and uses liquid as its templating language. For us, our website serves as our online presence, and a place for people to find out more about us and what we do. Its main purpose is to inform. As such, it is important that the site’s content be accessible regardless of browser used.

Being a content-only website, there wasn’t much need for a database-powered CMS, besides, our blog post authors were all engineers who were familiar with markdown already. Having the site written in vanilla HTML and CSS allowed for complete control over the markup structure and made creating custom layouts much more straight-forward.

The Liquid templating language confers a number of conveniences like the ability to utilise includes, for loops and basic boolean logic. Jekyll first introduced support for YAML-format data files in v1.3.0, then added support for JSON files in v2.1.0 and CSV files in v2.4.0. Data files, used together with Liquid, helps keep the source markup DRY.

Developers and their tools

All developers have their preferred way of working, be it on our own, or as part of a team, regardless of programming language or domain. For web development, a tool that I’ve found indispensable is Browsersync. It allows for the synchronised testing of websites across different devices as long as they are all on the same local network, as well as live reloading.

In addition, I also use gulp as my task-runner for Sass compilation and running Browsersync. There are numerous tools available that can perform similar functions as gulp, and it is up to you to select the one that suits your requirements best.

The tasks required for this particular website are:

- To build and serve the Jekyll site

- To compile

.scssfiles into.cssfiles and apply relevant vendor prefixes during compilation - To minify the

.cssfiles for production build - To watch relevant files for changes and reload the browser as necessary

The good thing about gulp is that it uses streams, allowing us to put a file into the stream to be processed then get an output at the end of it. gulp makes use of plugins that are written to do only specific things, allowing us to structure tasks into individual functions.

For example, below is the task for Sass compilation:

/**

* Compile files from _sass into both _site/assets/css (for live injecting)

* and assets/css (for future jekyll builds)

*/

gulp.task('sass', function () {

return gulp.src(['_sass/index.scss',

'_sass/posts.scss',

'_sass/team.scss',

'_sass/capabilities.scss',

'_sass/contact.scss'

])

.pipe(sass({

includePaths: ['scss'],

onError: browserSync.notify

}))

.pipe(prefix(['last 3 versions', '> 1%', 'ie 8'], { cascade: true }))

.pipe(gulp.dest('_site/assets/css'))

.pipe(browserSync.reload({stream:true}))

.pipe(gulp.dest('assets/css'));

});Cross-browser development strategies

For all the automated testing solutions I’ve encountered thus far, I haven’t found a tool that can best the eye-test. Perhaps in a few years things will be different. But for now, the most efficient way to test how something renders in a specific browser is to actually see it.

This is where it helps to have a variety of screens available to you during the development process. Most developers I know tend to develop using one specific browser throughout the development process, then test on other browsers after completing the bulk of the work. I’ve tried that approach as well, but found it resulted in a lot of rework down the line.

The most significant advantage of using Browsersync during development is the fact that I am able to observe the output of my code in a variety of browsers at the same time. Understandably, I must preface this by saying I’m fortunate enough to have access to a plethora of devices and screens. Because Browsersync also synchronises basic interactions like scrolling and clicking, it is immediately obvious when something is broken on a particular browser.

Here's the best-case setup of browsers (where there are multiple screens and devices available) I have open during development:

- Chrome

- Firefox

- Safari

- Edge

- Internet Explorer 11

- iOS webkit (technically all iOS browsers use webkit)

- Android browser

- Opera Mini*

The extreme data savings mode of Opera Mini is a bit tricky to test on. The rendering engine used in this mode is Presto, and the browser sends and receives requests through to Opera’s transcoding servers. Standards support for this mode is limited, with quite a few CSS properties not supported and Javascript not behaving as expected. Browsersync does not work on Opera Mini.

A way to get around this is to utilise Surge, a service offering free static web publishing via the command line and also supports continuous deployment using Git Hooks. By adding a git script to the package.json file, we can publish a specific directory to the Surge servers, accessible via a defined URL. Because the site is built on Jekyll, the target folder would be the _site folder.

"git": {

"scripts": {

"pre-push": "surge --project ./_site --domain THIS_DOMAIN_CAN_BE_ANYTHING.surge.sh"

}

}Feature queries are your best friend

For all the things Opera Mini does not support, the one thing it does have going for it, are feature queries. Feature queries are part of the CSS Conditional Rules Module Level 3, and it acts a test for whether an user-agent supports a particular CSS property:value pair. As with most conditional rules, and, or and not can be used in the query. If a particular feature query evaluates to false, the CSS declaration block within the feature query is ignored.

If you’ve accessed the site using both Chrome and Firefox, you will notice that the layout of the home page is slightly different. This is because Chrome supports CSS shapes, while Firefox does not at the moment. Here’s how the declaration block for that particular section looks like for browsers that support CSS shapes:

@supports (shape-outside: polygon(100% 100%, 0% 100%, 100% 0)) {

.l-services {

padding: 0;

position: relative;

a {

position: absolute;

right: 10vmin;

top: 50%;

transform: translateY(-50%);

}

}

.l-services__desc {

height: 75vh;

max-height: 25em;

p {

padding: 10vmin;

max-width: 60ch;

}

&:nth-child(1)::before {

display: block;

content: '';

shape-outside: polygon(20% 100%, 100% 20%, 100% 100%);

shape-margin: 1em;

clip-path: polygon(20% 100%, 100% 20%, 100% 100%);

float: right;

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

}

&:nth-child(2)::before {

display: block;

content: '';

shape-outside: polygon(100% 80%, 20% 0, 100% 0);

shape-margin: 1em;

clip-path: polygon(100% 80%, 20% 0, 100% 0);

float: right;

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

}

}

}For browsers that don’t support CSS shapes, there is a different set of styles applied to that same section so instead of the diagonal sectioning from CSS shapes, you see a tetris-block style layout instead. And both those layouts only apply on wider screen layouts with the use of width-based media queries.

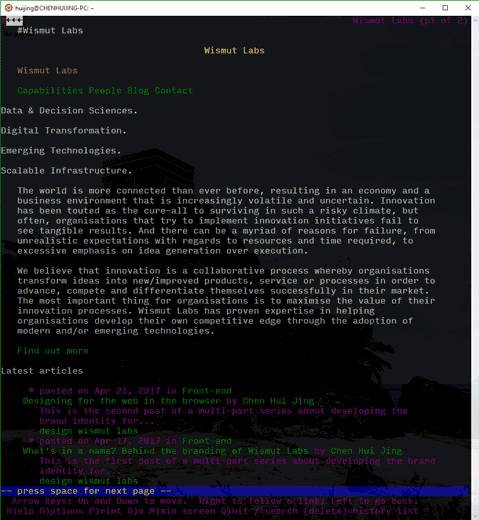

Strong foundations are key

CSS serves to enhance the look and feel of a website, but the underlying structure is determined by HTML, which forms the skeleton of the entire site. Having well-structured semantic HTML makes it easier to apply complex CSS, as well as minimise disruption to keyboard navigation and non-visual web browsing. One way to test for this is using a text-based browser like Lynx.

Conclusion

There are many considerations when it comes to designing and building a website. But some fundamental principles apply regardless of whether the site is a simple one-pager or a large site with thousands of pages. Admittedly, cross-browser compatibility is not a trivial effort, but there are ways we can ease the process so it is not an insurmountable hurdle. If a website’s main purpose is to inform, then it is all the more necessary that the content on that site be made accessible on as many browsers as possible.

And with that, we’ve reached the end of this series. Hopefully, this has given you a better understanding of the values our company is built on, as well as some insight into the process of developing the brand identity for Wismut Labs.

Read Part 1: What’s in a name? Behind the branding of Wismut Labs

Read Part 2: Designing for the web in the browser